Recruiting:

RECRUITING THE U. STATES ARMY 1808-1815

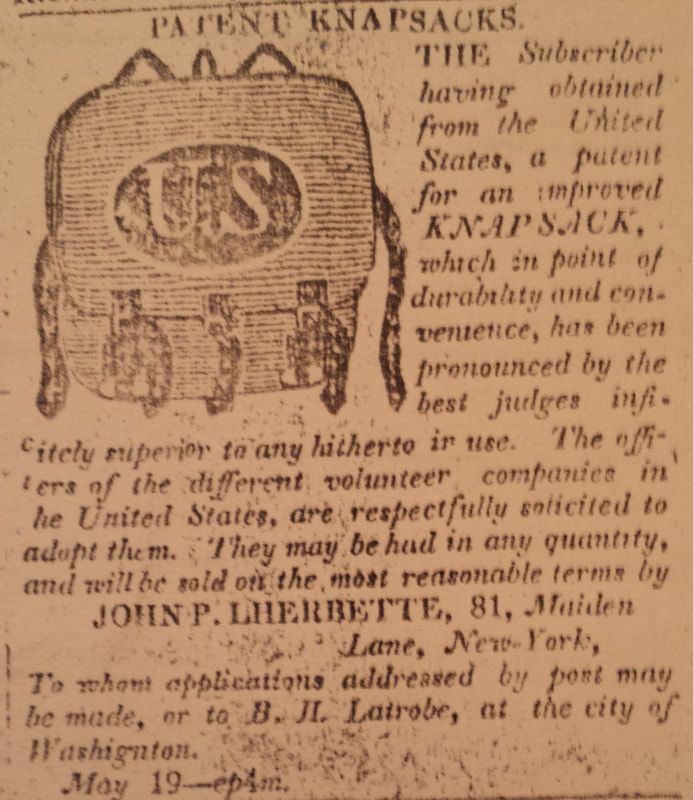

By David C. Bennett September 15, 2007 “The Rubicon is passed, and war is declared against our old and inveterate enemy, the British. The nation looks upon the act as a second Declaration of Independence,” as reported in the Missouri Gazette in St. Louis on July 11, 1812 upon the news of the Declaration of War against Great Britain. The Rubicon refers to a river in Northern Italy that Julius Caesar once crossed, starting a bitter war. To pass the Rubicon was to past the point of no return. [i] The National Intelligencer in Washington City reported that on June 19th, Declaration of War reached a recruiting party of the 5th Infantry about 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Captain Johnson immediately ordered his troops under arms and formed his detachment. The Captain “delivered an appropriate and animated address on the subject. Every eye seemed to beam with hope & the soldiers exulted at an opportunity to avenge the wrongs of their injured country. Every man swore to die at the point of the bayonet or live victoriously. The Officers drew their swords – marched to the centre and congratulated each other on the happy opportunity offered to display their valor and patriotism. This is the day they had wished for... A national salute was immediately fired, accompanied with appropriate martial music.”[ii] Stationed at Fort Osage, the westernmost outpost of the young United States, Captain Eli Clemson wrote in July 1812, to the Secretary of War. The Captain and his officers wrote a three page stinging indictment of the usefulness of the post, describing Fort Osage as a “Moth on the Publik purse.” Clemson went on to state that he would rather be fighting before the walls of Quebec than at a garrison “so cut off “from civilization. [iii] Despite the small size of the U. States army, their lack of experience, and the officer corps chock full of relics from the Revolutionary War, there was indeed a spirit and a determination to avenge the national pride. Yet enthusiasm for the War was not universal. Lt. Col. Daniel Bissell wrote on the 19th of September, that the “Yankees” in the Northeast displayed “a spirit amongst them, so unlike Americans, Yes, a sprit almost of Rebellion that will not do, in times like these, the Citizens to a man, after the Declaration of War ought to subscribe the Soldiers Creed, viz. not to ask why or wherefore they are to fight; it is the will of the Government, and I think absolutely necessary, it is true I would have liked to have had the Declaration been against the French also, but whatever is, is right with our Government...”[iv] Spoken like a true soldier. To understand the War of 1812 era, it is important to understand the soldier. Who were they, where were they born? Did they leave families behind? Did they enlist due to patriotic fervor or did they enlist for the money? To know the soldier of 1812 is to know the soul of the infant United States at War 1808-1815. As Congress increased the current “Peace Establishment” army, and prepared for War, written guidelines for recruiting the Regulars became necessary.[v] Though funds for recruiting were sent to Regiments and Companies by the Secretary of War, the actual business of recruiting remained a district or company level task. Before the war, it was common for a newly promoted Captain to be sent out to recruit his own company. Company officers were also transferred from one company to another, generally due to death. Infantry companies within a regiment were also frequently consolidated when company strength had been reduced due to death, desertion or discharge. However, the War of 1812 would not be fought only by the regular army, marines and the navy. Militia, volunteers and rangers would have a vital and crucial role during this war. And like the regular army, their record could be described as “the Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” As the War began, the small United States regular army, of approximately 6,000 men of all ranks, were scattered in coastal fortifications and small western garrisons. The perpetual business of recruiting had never ceased, but war displayed its vital importance. In Cities across the country an Officer with a trusty sergeant, a small recruiting flag and perhaps a musician set out to fill their companies and regiments. Captain William O. Allen of the 24th infantry was forced to hire a fifer at $10 a month for his recruiting rendezvous in St. Genevieve, Missouri.[vi] There has been a misconception that the regular army was comprised of no-good, property less scum of the earth. After all, the US was the land of “Milk and honey”, almost three quarters of the employed population were engaged in agricultural pursuits, and about 7% of the population lived in urban cities. On first blush, the US did not appear to be the kind of society where a large substantial Regular army could be recruited. The army during the War of 1812 was from a widely diverse group. 86.8% were native-born Americans. New England states furnished a third of the army, another third from the Southern States and slightly less than a third were from the Mid-Atlantic States. Population shifts already contributed to a situation where many men born in one state, were recruited in another. For example, three fourths of all men born in New Jersey were recruited in Pennsylvania and New York. Before the War, only “citizens” of the United States could be enlisted, but this changed on January 11, 1812, when any “able bodied man” could be enlisted. Where birthplaces were known, foreign-born recruits comprised 13 percent of the total, with the largest single group of 52.7 percent were natives of Ireland.[vii] In 1813, regiments were assigned to recruiting districts, thus historians today frequently label the 1st U. States Infantry for example, as recruited from New Jersey. However, the majority of the men in the 1st infantry were actually from Pennsylvania.[viii] The location of New Brunswick, New Jersey, as the primary recruiting depot for the 1st Infantry was partially due to Major Eli Clemson. The Major wrote to Col. Jacob Kingsbury on December 14, 1813, stating “...could not the few skeletons of Co’s of the 1st Infy. Be removed from the frontier where they have served for years be reunited and go to the scene of action...” [ix] Clemson was put in charge of recruiting for the regiment, and chose New Brunswick, New Jersey, as the recruiting rendezvous for the 1st Infantry. It was no coincidence that New Brunswick just happen to be where the Major was married in 1811, and was the home of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Oliver. It also didn’t hurt, that New Brunswick, New Jersey, had always been considered as “one of the best places for recruiting in the United States.”[x] At Fort Osage, one would expect that the occupation of Farmer would be the most common of all recruits. Farmers did make up 39%, yet artisans comprised 37% and Laborers were only 14.2%.[xi] The most common occupation found in Captain Clemson’s company at Fort Osage is that of shoe makers.[xii] This is not surprising when you factor in the economic hardship brought on during the years of 1807 to 1815. The diversity of the enlisted men’s occupations was utilized from the regiment to the Company level. Sawyers, tailors, bricklayers, shipwrights, joiner, shoemakers, seamen, hunters, laborers, clerks, and farmers were among the recruits of the army, and their skills were often relished by the recruiting officer.[xiii] When a soldier enlisted, his age, height, hair color, eye color, complexion and any distinguishing marks were recorded. The army was very proactive, and was simply preparing in case of desertion. The army would place an advertisement in the local paper with a reward such as the Missouri Gazette and Illinois Advertiser, dated October 15, 1814: “FIVE DOLLARS REWARD, Deserted, September 23d, from my detachment at Cape aux Gries, Samuel B. Gardner, a private about forty five years old, about five feet eleven inches high, thin visage and a very large nose; he is very much pock pitted, had on when he went away, leather pantaloons and a leather sailors jacket, carrying a rifle and a pistol.” [xiv] Gardner, a former regular soldier whose time of enlistment expired at Fort Osage, had enlisted in Colonel Henry Dodge’s Mounted Missouri Militia.[xv] The varied descriptions of complexion that were used in the enlistment records are very interesting. A few of these complexion descriptions were: pale, black, light, dark, natural, swarthy, yellow, brown, ruddy, mulato, florid, and fresh. Although a few historians have assumed that the complexion description of “black”, indicated a soldier of African descent, some men who were born in Germany and Ireland were also described with “black” complexion. In late 1814, a Captain in the 26th U. States Infantry enlisted over 200 men with African descent. The 27th U. States Infantry had a musician who was born in “San Domingo.” I have found at least one instance, where apparently a slave was recruited into the 40th U. States infantry. Private James Shirley was enlisted in Boston September 23, 1814, and I quote, “Slave to his master, a musician.” The issue of men of African descent being used as substitutes in the Army requires further research and investigation.[xvi] The age of the common soldier is also considerably older than one might expect. At the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, the average age in Captain Symmes Company of the 1st U. States Infantry was 30.[xvii] When the War began, recruits from 16 to 45 could be enlisted. An exception was made for musicians and men who were re-enlisting. In 1814, the recruitment age was changed to 18 to 40 years of age.[xviii] Later in 1814, when recruiting surged, a greater percent of farmers were enlisted than before. The average age of the farmer recruit was considerably younger than an artisan recruit. In 1813, at the tender age of 14, Jarvis Hanks enlisted as a drummer into the 11th U. States Infantry. Hanks recalled that a Sergeant visited his small village “beating up recruits” offering twenty dollars bounty and 160 acres of land for all those who enlisted for five years or for the duration of the war. The sergeant sent Hanks on to a recruiting depot where the Recruiting Officer promised him that he would not be forced to go into battle, and that he would remain as a recruiting musician in his own neighborhood. Musician Hanks was not retained in his own neighborhood, nor was the recruiting Officer’s promise honored to keep him out of battles. Hanks served till the end of the war with his regiment, surviving the bloody battles of Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane in 1814.[xix] John P. Gates, a 47 year old former interpreter for the army, enlisted into the 1st Infantry regiment on January 28, 1814. When it was rumored that the regiment was to leave the St. Louis area for Canada, Gates wrote to Governor William Clark of the Missouri Territory, informing the Governor that he had been enlisted in a drunken frolic at a St. Louis tavern, plus his recruiting officer had since died from alcoholism. Gates also informed the Governor of his large family, and that he, being a Canadian native, could not fire upon his own family. Though such claims of recruiting parties plying whisking on perspective recruits to get them drunk enough to enlist were common, not all such claims were true. Gates did have a large family, he was born in Canada, but his recruiting officer was still very much alive and serving as a 2nd Lt. in his own company. Needless to say, his letter to Governor Clark did not have the desirable affect.[xx] When the war began, the army pay had not changed since 1808. Privates earned $5 a month, musicians $6, Corporals $7 and Sergeants $8. The recruit earned an $8 bounty when enlisting and another $8 when mustered with his company. Upon termination of the enlistment, the soldier received three months pay and 160 acres of land. [xxi] The U. States Rangers, providing their own horse, rifle, and clothing earned $1.00 a day, or .75 when on foot. With common laborers earning $12 a month, and recruitment lagging behind, it was clear that the Government had to increase the pay in the regular army. Congress passed the Act of December 12, 1812, that gave a substantial pay increase to the enlisted men. Private’s pay increased to $8, musicians to $9, corporals to $10, and sergeants to $12.[xxii] After more Military failures and only a few land victories in 1813, Congress decided to revamp the enlistment bounties and also the term of enlistment in the regular army establishment. The recruit now had a choice: to enlist for five years or for the duration of the war only. There was an eighteen month term of enlistment in 1812 and a twelve month term offered in 1813 for the regulars. Rangers served one year terms. Additionally, Recruiting officers could now earn $4 for each recruit he signed up. The soldier now received a $24 bounty, receiving $12 when enlisted and $12 when mustered with his company. With enlistments continuing to drag and terms of enlistments ending for many soldiers, Congress once again decided to increase the pay. Against the advice of Secretary of War John Armstrong, not only was the bounty increased to $124, but $100 was paid upfront, and not when the soldier was discharged. The three month’s pay of $24 continued to be paid at the conclusion of their term. Almost 40% of all enlistments into the regular army occurred in 1814, after the increase of the bounty. [xxiii] The change had the desired affect, many new recruits came in; yet at the same time, desertions escalated as well. Officers also were now paid $8 for each man enlisted for five years, and only $2 if for the “duration of the war.” [xxiv] The 160 acres of land that the soldier received at the end of his enlistment can not be underestimated as an inducement for enlisting. For many young men, who were not the first born son expecting an inheritance, the promise of owning land convinced many a man to enlist. “Military Bounty lands” were located in the Old Northwest and also in the Missouri Territory. The regular Army enlisted man received a ration each day that consisted of: 1 ½ pounds of beef or ¾ pound of salted pork, 18 ounces of bread or flour, one gill of rum, whiskey or brandy, plus for every 100 rations to receive 4 quarts of vinegar, 4 pounds of soap, 2 quarts of salt, and 1 ½ pounds of candles[xxv]. Meals were issued twice a day. Fourteen year old Jarvis Hanks recalled, “Now was the first time I had ever slept on any thing harder than feathers, neither had I eaten any kind of meat unless it was previously well cooked. I now devoured raw pork with greediness and was obliged to sleep, sometimes on hay in a barn, and sometimes on the “soft side of a pine board”, as we used to say. I submitted to these inconveniences without murmuring; but was sorry enough that, for these, I had exchanged the comforts of my mother’s cupboard.”[xxvi] Once the new recruit joined his company, when was he no longer a recruit? Each new recruit was assigned to “an old soldier for a comrade”, who would teach him how to be a soldier, and how to clean “him self, arms & accoutrements.” The 1801 standing orders of the 1st Infantry were also very clear: a new recruit could, “not be struck, but when at the drill or Exercise and then only to rouse his Attention.”[xxvii] Each recruit would also have his hair “closely cut” as hair was not expected to be hanging over the coat collar nor projecting below the hat. Once the recruit was “smartened up” he was now available for guard duty, and he was no longer considered a recruit.[xxviii] Before the recruit could take the enlistment oath administered by a civilian Justice of the Peace, he had to pass a medical examination. The Surgeons Mate checked for ruptures, sore legs, scald heads, scurvy, liability to fits and habitual drunkenness.[xxix] If at a recruiting depot or rendezvous, the soldier was issued enough clothing to get him to his company. Each soldier was issued each year: 1 hat, 1 coat, 1 vest, 2 woolen overalls, 2 linen overalls, 4 pairs of shoes, 4 shirts, 2 pair of socks, 2 stockings, 1 blanket, 1 stock and clasp, 1 pair of gaiters, 1 linen frock, 1 linen “trowsers”, 1 knapsack.[xxx] The soldier also drew a .69 caliber iron mounted Springfield musket, pattern of 1808 accoutrement s, canteen, and haversack. The soldier also received a small pocket-book to record every time he received an issue.[xxxi] When the company descriptive book was updated with a clothing issue, the soldier’s book would also be updated. During company inspections, the soldier would provide his book to the 1st Sergeant who would compare what was issued with what the soldier then possessed. George Yount remembered when he had enlisted in a Missouri Militia company, and I quote “My brother in law made me join the rifle company of which Morris Young was Captain...my father gave me my outfit, for we had to find our own equipment, rifle, tomahawk and scalping knife, besides a horse.”[xxxii] On July 19, 1812, three hundred and twenty muskets complete with bayonets and “cartooch” boxes were issued to a detachment of the Indiana Militia.[xxxiii] The Missouri Territory Militia laws dictated, “...no citizen soldier may be ignorant of the manner in which the law requires him to be equipped, he is reminded that it is his duty to provide himself with a good musket, with bayonet and belt, or a fusil, two spare flints, a knapsack, powder horn and pouch, with 20 balls, and a quarter of a pound of powder.”[xxxiv] Despite the Militia law that the citizen was to provide their own weapon and accouterments, that was not always the case. The Missouri Gazette reported on August 13, 1814, that “Those who may have in their possession public swords, Rifles, Muskets and bayonets, are directed to deliver them forthwith to the Commander in Chief, or to the Officer who may be appointed to receive them in St. Louis.”[xxxv] Thus, the recruits of the War of 1812 whether they were Regulars, Militia or Volunteers, were given the oath, clothed and equipped, and sent on to defend and protect the United States. The U. States army included men from diverse backgrounds and previous occupational skills. They enlisted for all of the same reason soldiers enlist today, patriotic duty and money. Some men were on keel boats going up the Illinois, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers engaged against hostile Indians. Some men were on the Northern border with Canada, others on the Eastern seaboard while others still, were serving in the South. Even though it is only seven years short of 200 years from that memorable year of 1812, the army still recruits, and the recruits are still taught to be soldiers. Just like their modern day counterparts, the soldier of 1812 gave their oath, that he would “bear true faith and allegiance to the United States of America.” [xxxvi] |

Recruiting:

1st Infantry Wool Bunting hand sewn 15 Star Garrison Flag, 10 x 15 feet and three pound gun. Bicentennial May 25 2013

Come All You Young Heroes! Your Country Calls! "Seeking Men of Patriotism, Courage, and enterprize to join the U. States Army. The Duties will be pleasant, the payment prompt, the cloathing elegant, and the provisions good. Tall, straight, sturdy men of reputation and industry and morals will be readily received to defend our Country. Lazy, drunken, thievish rascals need not apply – we do not wish to rob the Gallows of your services." The 1st Regiment of U.S. Infantry under the able guidance of Captain Eli B. Clemson is seeking recruits to fill its ranks. None but citizens of the United States need apply to aid in revenging the wrongs committed upon us and firmly establishing those glorious rights which our forefathers have triumphed or died for! A good drummer and fifer will meet with good encouragement. The 1st U.States Infantry regiment Clemson - Symmes company, recreated, is a living history group dedicated to educating the public about the US Army in the Early Republic. We travel to events throughout the US and Canada as well as sponsor the War of 1812 in the West History Symposium, the longest continually running War of 1812 history conference in the United States. Contact Dave Bennett for more information at [email protected] Updated 16 January 2018 The site is copyrighted 2018. Enlisted Mens shirts:

"Purveyors Office Dec. 28 1810

One yeard in length from the bottom of the collar to the bottom of the tail hem. the width to be the whole width of the dowlass or creas linen. The sleeves to be 20 inches long the collar to be 17 inches long the collar to be 3 and 3/4 wide. The collar to have two buttonholes. The wristbands to be 9 inches long. The shoulder straps to be 9 and 1/2 inches long. The gusset 4 inches and 3/4 square. The Bosom ruffle 2 inches and 1/2 wide. The collar to have two buttons. The sleeves to be 9 1/2 inches wide. These were the proposed sizes but if the shirts in the arsenal are larger they must be made as large as them this year." The enlisted man's shirt is basically a one size shirt, 16 Neck and 34 sleeeve. One size would be used by the US Army till the Civil War. Seams are 1/4 inch felled to 1/8 inch. "Philad. Octr. 27 1813 Be Pleased to issue each of the following persons the following materials to make Private shirts...1500 yds of cotton shirting....50 yds of Muslin for frills....6 lbs of cotton thread....1 lb of sticking thread and 1000 shirt moulds." Records of the Quartermaster General Supply orders issued Volume 1 RG 92 The shirt buttons were wooden mould buttons covered with the shirting. Only two buttons at the throat, the cuffs would be secured with cuff links made from buttons.

| ||||||||||||

|

|